The generous U.S. unemployment benefits rolled out to blunt the economic harm caused by the coronavirus could have an unintended effect: it may actually be an incentive for companies to choose layoffs rather than keep staff on their books.

That’s at odds with a government-backed loan forgiveness program set to launch for small and medium-sized firms that opt against job cuts, so long as the bulk of the money is used to keep staff on at full salary.

The number of Americans filing for unemployment benefits last week shot up to more than 6 million, a record high, Labor Department data on Thursday showed. Millions more are set to claim in the coming weeks as major parts of the United States economy remain shut down until the death toll from the virus shows signs of abating.

The CARES Act passed by Congress a week ago was designed to keep businesses and workers from economic freefall. For workers losing their jobs, an unprecedented expansion in unemployment benefits until the end of July was put in place.

On Friday millions of firms are expected to apply to lenders approved by the Small Business Administration for low-cost loans that the government says will be forgiven if employers keep people on their payroll through the end of June.

But businesses are already grappling with a tricky equation: which route is best for them and their employees?

“Unemployment insurance, at least short term, is quite generous so the firms may decide that that’s a better way to go,” said former Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen at a Brookings Institute event earlier this week.

Employers have to weigh up the cost to them of keeping their businesses open even if they have limited or no revenue versus at least some of their workers temporarily earning more by seeking unemployment benefits.

A blanket provision of a $600 weekly unemployment benefit on top of each state’s replacement rate of lost wages, which averages about 45% up to a certain salary cap, was implemented by Congress to quickly make more workers whole on their lost paychecks.

Though benefits vary by state, the average unemployment benefit plus the $600 pandemic payout exceeds the weekly median pay of $933. Perhaps 56 million or more workers would be better off temporarily receiving unemployment benefits than staying on the job, Labor Department data shows https://reut.rs/39IbGQ0.

Chief among them are retail and food service industry employees, who have already been hard-hit by states putting in place “stay at home” orders.

Many economists say a better designed unemployment program would have been to compensate a percentage of wages lost, based on a person’s previous salary, but at a much higher rate than during normal times. They point to European programs, such as in the UK, where the government has said it will pay 80% of workers’ salaries for firms that keep them on.

Outdated computer systems made it too difficult for states to individually calculate different payments per U.S worker.

AN SBA LOAN OR NOT?

The so-called Paycheck Protection Program, administered by the Small Business Administration (SBA), is aimed at keeping businesses with less than 500 employees from having to fire their employees.

Lenders have said they have been inundated as businesses seek a slice of the initial tranche of $350 billion the U.S. government has set aside. Each loan is capped at $10 million and will be distributed on a first-come, first-served basis.

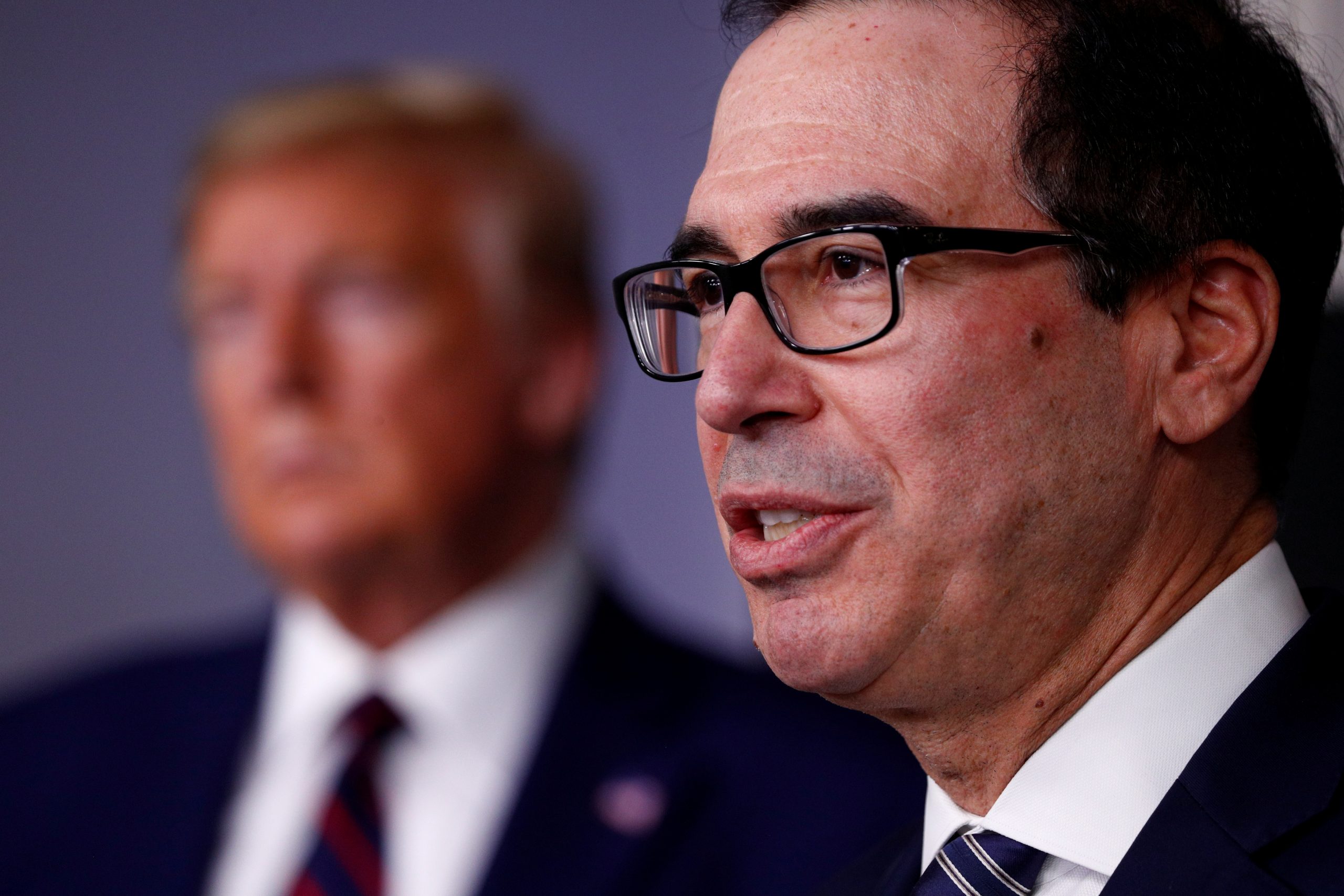

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said on Thursday the enhanced unemployment benefits are targeted at workers laid off from bigger companies that can’t afford to pay them and don’t have access to the loan program.

Small businesses, including restaurants, would want to take the loans because they will cover not just payroll but also overhead like rent and utilities, he said.

David von Storch, president and founder of Urban Adventures Companies, which owns the VIDA gym chain as well as Bang Salons in Washington DC, said he plans to apply for the SBA loan, while still pursuing layoffs for employees who would be better off going on unemployment benefits than continue to get his paychecks.

“Under this scenario, we would continue to pay the health insurance of these employees and bring them back as soon as we reopen,” he said.

It also depends on how long businesses think the lockdown orders will last, and whether the economic damage will dampen demand even when they can re-open.

“If their business hasn’t dried up completely right now, then the incentive to jump through the hoops to get a loan is much stronger,” said David Wilcox, former head of the Federal Reserve’s research and statistics division, now at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

That uncertainty is making firms “stressed” about what is the best option for both their business as well as employees in the short term, said Holly Wade, director of research for the National Federation of Independent Businesses, which represents hundreds of thousands of small and mid-size firms.

It’s one thing for those firms to take out the loan and then business picks up after two months, according to Wade. The bigger issue is if demand deteriorates, and they have to close.

“That’s a huge concern,” she said.

(Reporting by Lindsay Dunsmuir, Howard Schneider, Lucia Mutikani and David Lawder in Washington; Ann Saphir in San Francisco; Editing by Dan Burns and Edward Tobin)

Continue with Google

Continue with Google