Vernon Jordan, who grew up in the segregated South to become an influential leader in the American civil rights movement, Washington politics and Wall Street, has died at age 85, according to media reports citing his family.

Jordan, who in 1980 was badly wounded by a white supremacist sniper in Indiana, died Monday night, the reports said.

Jordan “passed away peacefully last evening surrounded by loved ones. We appreciate all of the outpouring of love and affection,” his daughter Vickee Jordan said, according to CNBC and New York Times reporter Andrew Ross Sorkin. CBS and CNN also reported his death, citing multiple family members.

The NAACP’s Legal Defend Fund, where Jordan served on the board of directors, in a statement on Tuesday said it was “deeply saddened” by his death, calling him “an esteemed attorney and leader who helped drive the advancement of civil rights in America over a venerable career.”

Jordan worked well into his 80s, going back and forth between the jobs at the Gump Akin international law and lobbying firm in Washington and the Lazard financial management firm in New York. Representatives for Gump Akin did not respond to a request for comment on the reports.

Jordan’s role as a Washington insider took him all the way to the White House, where he was a close friend, golfing buddy and adviser to President Bill Clinton in the 1990s.

He never held a formal government job, but no one knew better than Jordan how favors, access and requests worked in Washington. In 2018 the Financial Times called him “one of the most connected men in America.”

Jordan grew up in a housing project in Atlanta before his family bought a home and he was the only black person in his class at DePauw University in rural Greencastle, Indiana.

After graduating, Jordan earned a law degree from Howard University and returned to Atlanta to work for a civil rights attorney. Among his cases was one that integrated the University of Georgia and Jordan helped escort his two young black clients past jeering protesters on their first day of class.

Jordan later went to work for the NAACP and the United Negro College Fund before becoming head of the National Urban League in 1971.

‘ROSA PARKS OF WALL STREET’

After gains in voting rights and equal access laws, Jordan’s approach was to push for greater economic opportunities for blacks, even in corporate boardrooms.

At an Urban League event Jordan said he told the organization’s corporate benefactors, “Don’t just give us money and don’t just show up for the Equal Opportunity Day dinner. That is not enough when you look at black consumer power in this country. It’s not enough for you to come and shake our hands and be our friends. We want in.”

Under his leadership, the Urban League began issuing its annual State of Black America reports to assess the social and economic status of black Americans.

U.S. companies such as American Express, Xerox, Dow Jones, Bankers Trust, RJR Nabisco, Revlon and Sara Lee put him on their boards, where he was often the only Black member.

“He is kind of the Rosa Parks of Wall Street,” Harvard historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. said in an interview with the Bloomberg news service. “He realized that the first phase of the modern civil rights movement was fighting legal segregation but the roots of racism were fundamentally economic.”

Jordan was close to President Jimmy Carter in the 1970s, and Carter reportedly offered him cabinet jobs. Jordan would eventually become critical of Carter, saying he had not delivered on his economic promises to blacks.

In 1980 Jordan was badly wounded as he exited the car of a white woman who was an Urban League member in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Joseph Paul Franklin, a former Ku Klux Klansman and member of the American Nazi Party who was convicted of a series of race-related murders, admitted to the ambush but was acquitted. He told authorities he hated interracial couples.

After 10 years at the Urban League, Jordan wanted something different and joined Gump Akin. Tall and imposing, he earned a reputation for being a charming and persuasive “Washington wise man.” After Clinton was elected president in 1992, he chose Jordan, whom he had known since the early 1970s, to head his transition team.

In 1999 Jordan became a senior managing director at Lazard with the goal of bringing in new business and advising executives.

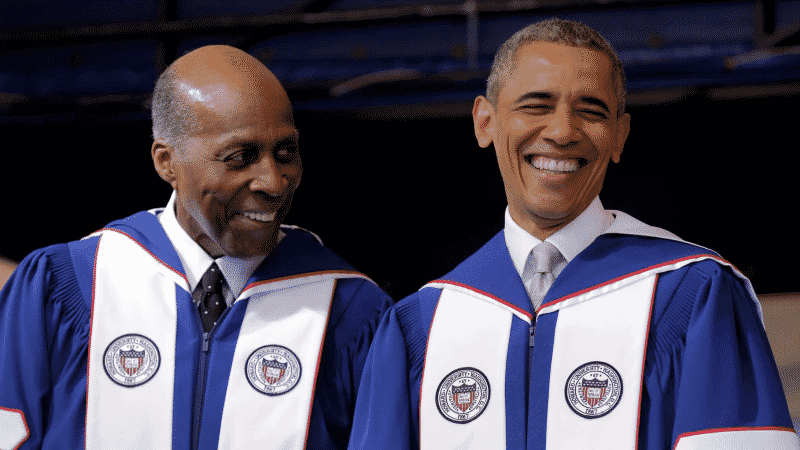

In 2008 when Barack Obama was running to be the first black president, Jordan stuck by his longtime friends and supported Hillary Clinton for the Democratic Party’s nomination. According to the Financial Times, Jordan told Obama, “I am too old to trade friendship for race.”

Jordan’s first wife, Shirley Jordan, died of multiple sclerosis in 1985. They had one child. In 1986 he married Ann Dibble.

(Additional reporting by Susan Heavey; writing by Bill Trott; Editing by Chizu Nomiyama and Steve Orlofsky)