The police chief of the Uvalde, Texas, school district, Pete Arredondo, defended his handling of the May 24 mass shooting at Robb Elementary School.

Many individuals “who just don’t’ know the whole story” were “making their assumptions on what they’re’ hearing or reading,” Arredondo told The Texas Tribune in an interview published Thursday.

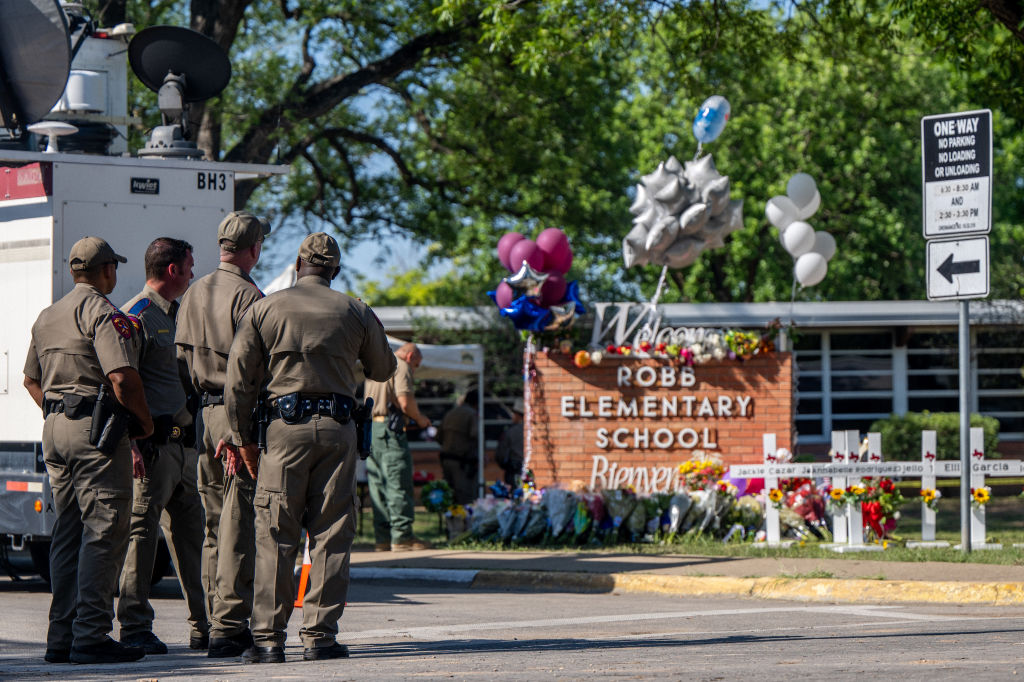

On May 24, 18-year-old gunman Salvador Rolando Ramos walked into Robb Elementary School carrying a semi-automatic rifle. Ramos opened fire, killing 19 children and two adults and wounding several others until Border Patrol agents killed him.

That it was a team of Border Patrol agents who shot the gunman and not police officers who were present much earlier at the scene raised questions about what the local police department did during the incident.

The director of Texas’ Department of Public Safety, Stephen McCraw, confirmed to journalists in a news conference later that week that there was a 40-minute delay in officers’ response to the gunman.

“The on-scene commander at the time believed that it had transitioned from an active shooter to a barricaded subject,” McCraw said, calling the decision to wait for backup and not directly engage the shooter “a wrong decision.”

Although McCraw did not name Arredondo as the specific “on-scene commander” that day, multiple reports identified him as the “incident commander” during the shooting.

Arredondo told the Tribune that he did not consider himself to be the incident commander that day. The chief, however, said he and his colleagues were willing to confront the shooter, pushing back against criticism of cowardice.

“The only thing that was important to me at this time was to save as many teachers and children as possible,” Arredondo said, according to the Tribune.

“Not a single responding officer ever hesitated, even for a moment, to put themselves at risk to save the children,” Arredondo said. “We responded to the information that we had and had to adjust to whatever we faced. Our objective was to save as many lives as we could, and the extraction of the students from the classrooms by all that were involved saved over 500 of our Uvalde students and teachers before we gained access to the shooter and eliminated the threat.”

The 40-minute delay in officers’ response, according to Arredondo, was because officers needed to find the key to the classroom door, which was “reinforced with a hefty steel jamb, designed to keep an attacker on the outside from forcing their way in,” so they could not open the door by simply kicking it in, Arredondo said, according to the Tribune.

Hence, Arredondo and his colleagues spent about an hour in the school’s hallways, waiting for the keys and tactical gear. Arredondo asked officers to back off from near the door for 40 minutes to avoid provoking gunfire from Ramos, the chief told the Tribune.

At that point, the gunman was firing sporadically. “The ammunition was penetrating the walls at that point,” Arredondo said. “We’ve got him cornered, we’re unable to get to him. You realize you need to evacuate those classrooms while we figured out a way to get in.”

After the keys arrived, Arredondo said he tried dozens of them, one by one, to find the right one and save the children. “Each time I tried a key I was just praying,” Arredondo said, according to the Tribune. Once the door was unlocked, officers went in and shot Ramos.

“I didn’t issue any orders,” Arredondo said, denying claims by DPS officials, who said he had declared the situation a ‘barricaded subject’ situation. “I called for assistance and asked for an extraction tool to open the door,” Arredondo said.

Arredondo also addressed reports that he did not have a radio on him when went toward the campus. Arredondo said that he had removed the radio to prevent it from being a burden when he ran to the school. That decision hampered his ability to communicate with other law enforcement officers and agencies on the scene.

Arredondo’s responses did not satisfactorily address the concerns raised by experts the Tribune spoke to. The outlet reached out to seven law enforcement experts, six of whom said Arredondo made some wrong decisions during the incident.

“I’ve never heard anything like that in my life,” Steve Ijames, a police tactics expert and the former assistant police chief of Springfield, Missouri, said of Arredondo’s rationale behind abandoning his radio. Ijames said that officers are trained not to get rid of their primary communication device.

One expert the Tribune spoke to, however, was sympathetic toward Arredondo.

“There’s no manual for this type of scenario,” former Victoria police chief Bruce Ure said. “If people need to be held appropriately accountable, then so be it. But I think the lynch-mob mentality right now isn’t serving any purpose, and it’s borderline reckless.”

Despite the criticism and death threats he received, Arredondo said he was proud of his and his colleagues’ response.

“No one in my profession wants to ever be in anything like this,” Arredondo said. “But being raised here in Uvalde, I was proud to be here when this happened. I feel like I came back home for a reason, and this might possibly be one of the main reasons why I came back home. We’re going to keep on protecting our community at whatever cost.”

This article appeared originally on The Western Journal.

Continue with Google

Continue with Google