A new report indicates that the Biden administration’s highly publicized sanctions against Russia have worked too well — to the point where officials are now trying, with limited success, to convince U.S. companies to buy and carry Russian products to lessen the “collateral damage” that’s been done to the American economy.

“[S]ome Biden administration officials are now privately expressing concern that rather than dissuading the Kremlin as intended, the penalties are instead exacerbating inflation, worsening food insecurity and punishing ordinary Russians more than Putin or his allies,” Bloomberg reported.

According to sources Bloomberg did not name, the Biden administration has been “encouraging” businesses in the agriculture, medicine and telecommunications sectors to stay connected to Russia.

For instance, “[t]he US government is quietly encouraging agricultural and shipping companies to buy and carry more Russian fertilizer, according to people familiar with the efforts, as sanctions fears have led to a sharp drop in supplies, fueling spiraling global food costs,” Bloomberg reported Monday.

But domestic businesses, fearful of being hit with costly sanctions, are reluctant to do so.

Last month, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control said companies could continue to pay taxes, fees and import duties linked to doing business in Russia.

“The message was clear: Doing business in Russia is allowed, provided companies aren’t working with sanctioned entities,” Bloomberg wrote.

Adam Smith, a former senior adviser to OFAC, noted that agriculture, medicine and telecommunications were left out of a recent order banning consultants from doing business with other sectors of the Russian economy.

The Bloomberg report said that the administration was alarmed at the damage done when the imposition of sanctions triggered a mass corporate flight out of Russia, which then triggered supply chain issues and shortages, noting that “collateral damage from the sanctions has been wider than expected. “

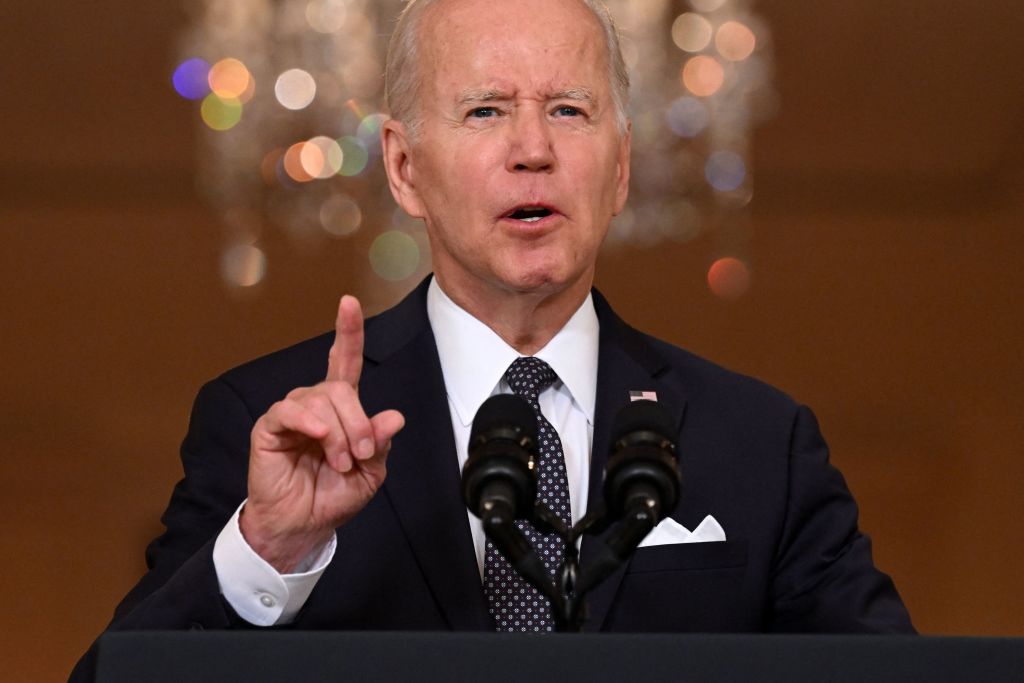

That collateral damage includes energy costs that have spiraled, fueling inflation that has become a political liability for President Joe Biden.

Justine Walker, the head of global sanctions and risk at the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists, said companies fear being caught up in the webs of sanctions from the U.S. and the European Union.

“Because we just have so many changes at once, governments are not able to step in and give precise clarification and we are seeing many, many examples of authorities coming to different positions,” Walker said. “Companies ask, ‘Should we be applying sanctions to this entity?’ and the government will come back and say, ‘You need to make your own decision.’”

The Biden administration said it has not fumbled with its imposition of sanctions.

“The story that the sanctions are causing the problem, I think, is deeply misleading,” Ambassador Jim O’Brien, head of the State Department’s Office of Sanctions Coordination, said.

“Sometimes companies are confused about what’s allowed and what’s not, and we will try to clarify so that they are able to go forward. But we are also working proactively by trying to inform companies about what they are allowed to do,” he said.

The Yale Chief Executive Leadership Institute estimates that 1,000 companies pulled out of Russia after the sanctions were imposed.

Smith said because companies pulled out on their own, sometimes selling assets at fire-sale prices, lifting sanctions does not mean they will return.

He said the flight of American companies from Russia “does some psychological harm to Russia, psychological injury.”

However, he added, “at the end of the day, is removing elements of US soft power where the US wants to be?” he said.

This article appeared originally on The Western Journal.

Continue with Google

Continue with Google