In his brief three-month campaign for president, Michael Bloomberg poured nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars into building an advertising and data-mining juggernaut unlike anything the political world had ever seen.

But a big part of the strategy hinged on a wildcard named Joe Biden.

Bidens’s resurgence after a dominant victory on Saturday in South Carolina has upset that calculation in the critical do-or-die sprint before “Super Tuesday,” when Democrats in 14 states vote for the candidate to challenge Republican Donald Trump in November’s election.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. The billionaire former New York City mayor’s strategy was partly based on expectations that Biden would falter in the first four states. Bloomberg, who skipped the early contests, would then become the moderate alternative to frontrunner Bernie Sanders, the Vermont senator and self-described democratic socialist.

Although Biden underperformed in Iowa and New Hampshire, he did better in Nevada and bounced back in South Carolina on a wave of African-American support to end Sanders’ winning streak and establish himself as the race’s top-tier moderate Democrat.

Meanwhile, Bloomberg’s once-ascendant campaign has struggled after he came under fire in debates over past comments criticized as sexist and a policing policy he employed as New York’s mayor seen as racially discriminatory. He has apologized for the policing policy and for telling “bawdy” jokes.

Advisors and people close to the Bloomberg campaign say they are still in the race and rebuff criticism that he’s splitting the moderate vote and making it easier for Sanders to win.

The campaign’s internal polling showed that Bloomberg’s supporters have both Biden and Sanders as their second choices, contrary to the perception that he was mostly peeling off Biden’s support, one campaign official said.

If Bloomberg dropped out, Sanders would be on a stronger path to victory, the official said.

Bloomberg has hovered around 15% in national polls, suggesting he will earn some delegates on Tuesday. If those polls are correct, he will likely earn fewer delegates than Sanders and Biden.

Another moderate, Pete Buttigieg, dropped out on Sunday, driven in part by a desire not to hand the nomination to Sanders, a top adviser said. “Pete was not going to play the role of spoiler.”

Bloomberg, however, has vowed to stay in the race until a candidate wins a majority of delegates needed to clinch the nomination. His campaign has spent heavily on advertising in states that vote on Tuesday, when a third of the available delegates that help select a Democratic nominee are awarded in a single day.

And it’s pinning some of its hopes on Virginia, the fourth-biggest state at stake on Tuesday and a key testing ground for Bloomberg. He made his first campaign visit here last November, and has visited another six times since. Last week, his campaign had hopes he could win or come close.

But even that plan is facing new headwinds.

After Biden’s win in South Carolina, the former vice president picked up endorsements from former Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe and Virginia Senator Tim Kaine, the 2016 Democratic vice presidential candidate — underlining how Biden’s comeback is drawing establishment Democrats who might have otherwise backed Bloomberg.

Dan Blue, a prominent Democrat in the North Carolina State Senate who endorsed Bloomberg last week, said Biden’s strong showing in South Carolina reset the race. But he said he still believes that Bloomberg can win by playing the long game and gradually accumulating delegates.

“There’s no question in my mind that this thing is very fluid and not absolute,” he said.

‘HUGE NATURAL EXPERIMENT’

Bloomberg’s heavy advertising spending, however, makes him a uniquely powerful candidate even if he lags in opinion polls.

He has spent more than half a billion dollars on ads ahead of Tuesday, more than four times the combined ad spending of his four remaining main rivals – Sanders, Biden, Senator Elizabeth Warren and Senator Amy Klobuchar, according to data from ad tracker Advertising Analytics.

The biggest chunk was spent in Super Tuesday states, $214 million through Feb. 25, including more than $63 million in California and $50 million in Texas, where one analysis said 80 percent of the ads were Bloomberg’s.

Already, Bloomberg has spent more on television ads than Donald Trump and Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton did in their entire 2016 campaigns.

“It’s truly astonishing,” said Michael Franz at Bowdoin College in Maine, a leading researcher on political advertising. “He is giving us a huge natural experiment.”

Many of his ads feature Trump, mocking the president as a “bully.” Others introduce his life story. When he drew criticism for sexist comments and past treatment of women on the job, one ad countered with endorsements from longtime women employees.

The campaign also has pushed beyond old frontiers with digital spending. More than $106 million have been poured into Google and Facebook ads, according to disclosures by the social media giants.

Without a young network of enthusiasts on social media like the one enjoyed by Sanders, Bloomberg has tried to boost his online presence by paying for one: he has hired influential meme accounts to post messages on Instagram, and paid others $2,500 a month to share pro-Bloomberg messages on texts and social media.

Inside his campaign headquarters in New York, the staff of Hawkfish, a start-up digital analytics company, sift through huge tranches of voter data to help chart his campaign strategy.

Bloomberg decided Hawkfish was necessary because Democrats haven’t kept up with Trump’s ability to target voters and bombard them with messages, said Dan Kanninen, the campaign’s states director. “It’s a very potent, very difficult-to-overcome weapon.”

‘HOW MUCH CAN IT BUY HIM?’

His unprecedented spending has likely fueled his rise in public opinion polls from just around 5% when he entered the race on Nov. 24 to about 16% in recent polls.

“The question is, how much can it buy him, and there’s definitely a ceiling,” said Amanda Wintersieck, a political science professor at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia.

In South Carolina, where he was not on the ballot but had still spent $2.3 million on advertising through Feb. 25, two thirds of the primary voters said they viewed Bloomberg unfavorably, according to Edison Research exit polls. About 77% and 51% of these voters had favorable views of Biden and Sanders, respectively.

The spending has also provided a target for opponents who say Bloomberg is stark proof that the wealthy wield too much influence over U.S. elections.

In conversations with dozens of mostly Democratic voters across seven states last week, Reuters found that Bloomberg’s spending blitz had won him a little enthusiasm, and some respect. “He might be the one,” said Garolyn Greene, 41, as she waited at a bus stop in Houston where Bloomberg held a rally on Thursday.

Others were less forgiving. Bloomberg has apologized for overseeing an increase in the use of a police practice called “stop and frisk” in New York City that disproportionately affected black and other racial minority residents.

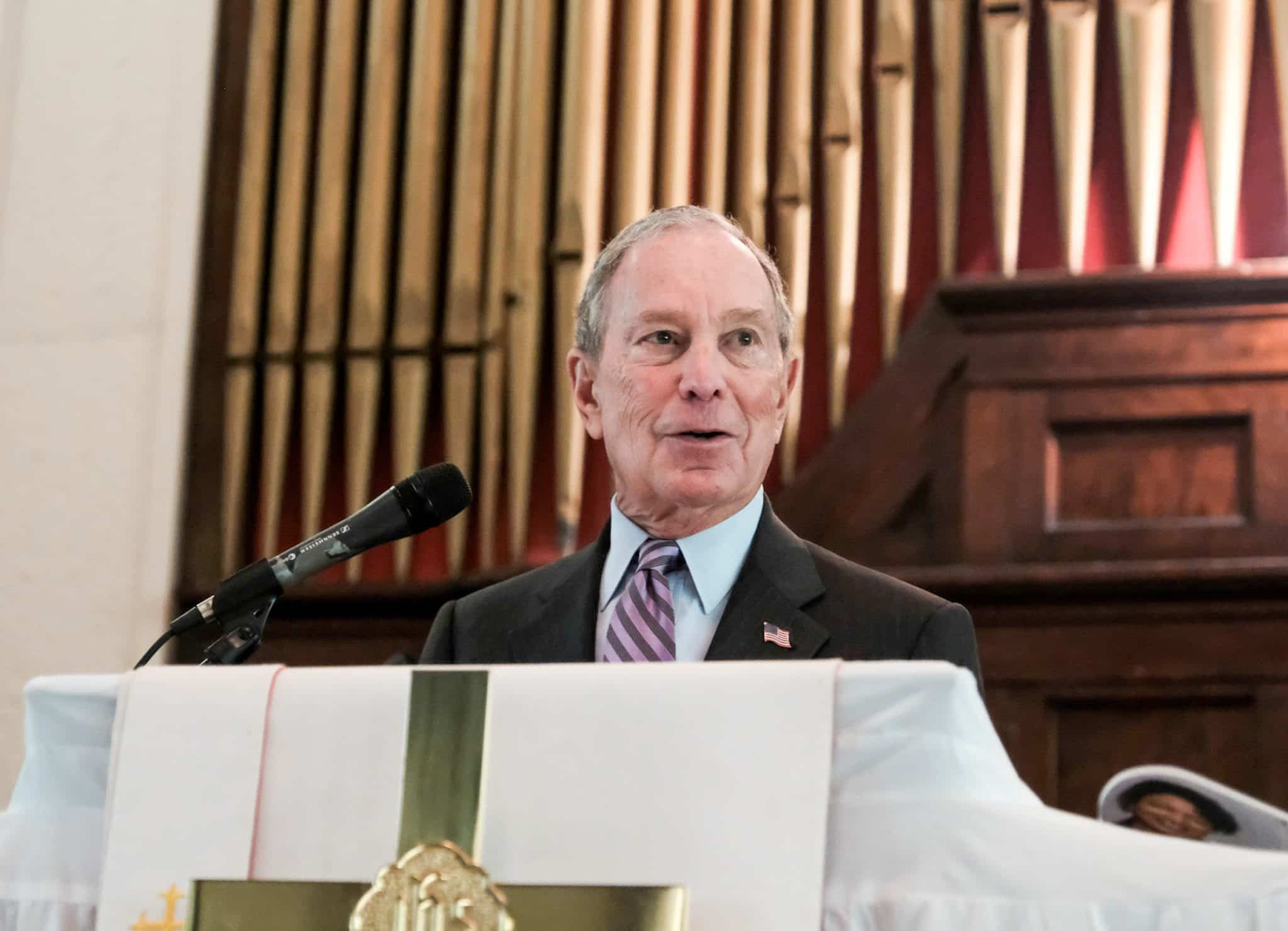

On Sunday, as Bloomberg started to speak about racial inequality at a chapel in Selma, Alabama — one of the 14 Super Tuesday states — about 10 people, mostly black, stood up and turned their backs. Biden was seated in a place of honor with the pastor at the same church.

“I think it’s just an insult for him to come here,” said Lisa Brown, who is black and a consultant who traveled to Selma from Los Angeles, referring to Bloomberg.

The incident underlined Bloomberg’s continued struggles to win over black voters — a core constituency for the Democratic Party.

A VIRGINIA BATTLEGROUND

Bloomberg’s supporters say they hope his spending will deliver dividends in battleground states that favor moderates like Virginia, where some polls put him ahead of Biden but at a close second behind Sanders.

Bloomberg made friends in Virginia long before his campaign, spending millions to elect Democrats to state offices and congressional seats, culminating with Democrats taking control of the state legislature last November. Last week, those legislators gave final approval to a sweeping set of gun control laws – a signature cause for Bloomberg.

“I think people are appreciative,” said Lori Haas, Virginia director of the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence and a Bloomberg supporter.

Bloomberg has opened seven field offices in the state, part of a national network of offices and paid staff that has far outpaced his rivals. The campaign had more than 2,000 paid workers and 214 offices in 43 states, not counting the several hundred in his New York headquarters, said Kanninen, the campaign’s states director.

Whatever happens on Tuesday, Bloomberg and his campaign staffers have been stressing that he will keep spending into the fall to defeat Trump, whether he’s the candidate or not.

“Someone said you shouldn’t be spending all that money,” Bloomberg said on Saturday at a get-out-the-vote rally aimed at women in McLean, Virginia. “I said, ‘Yes, well I’m spending it to remove Donald Trump,’ and he said, ‘Well, spend more.’”

(Additional reporting by Joseph Ax, Elizabeth Culliford, Tim Reid and Trevor Hunnicutt Editing by Soyoung Kim and Jason Szep)

Continue with Google

Continue with Google