Before she suspended in-person campaigning in March, Arati Kreibich was knocking on upwards of 1,000 doors every weekend in the northern New Jersey congressional district she hopes to wrest away from a moderate Democratic incumbent.

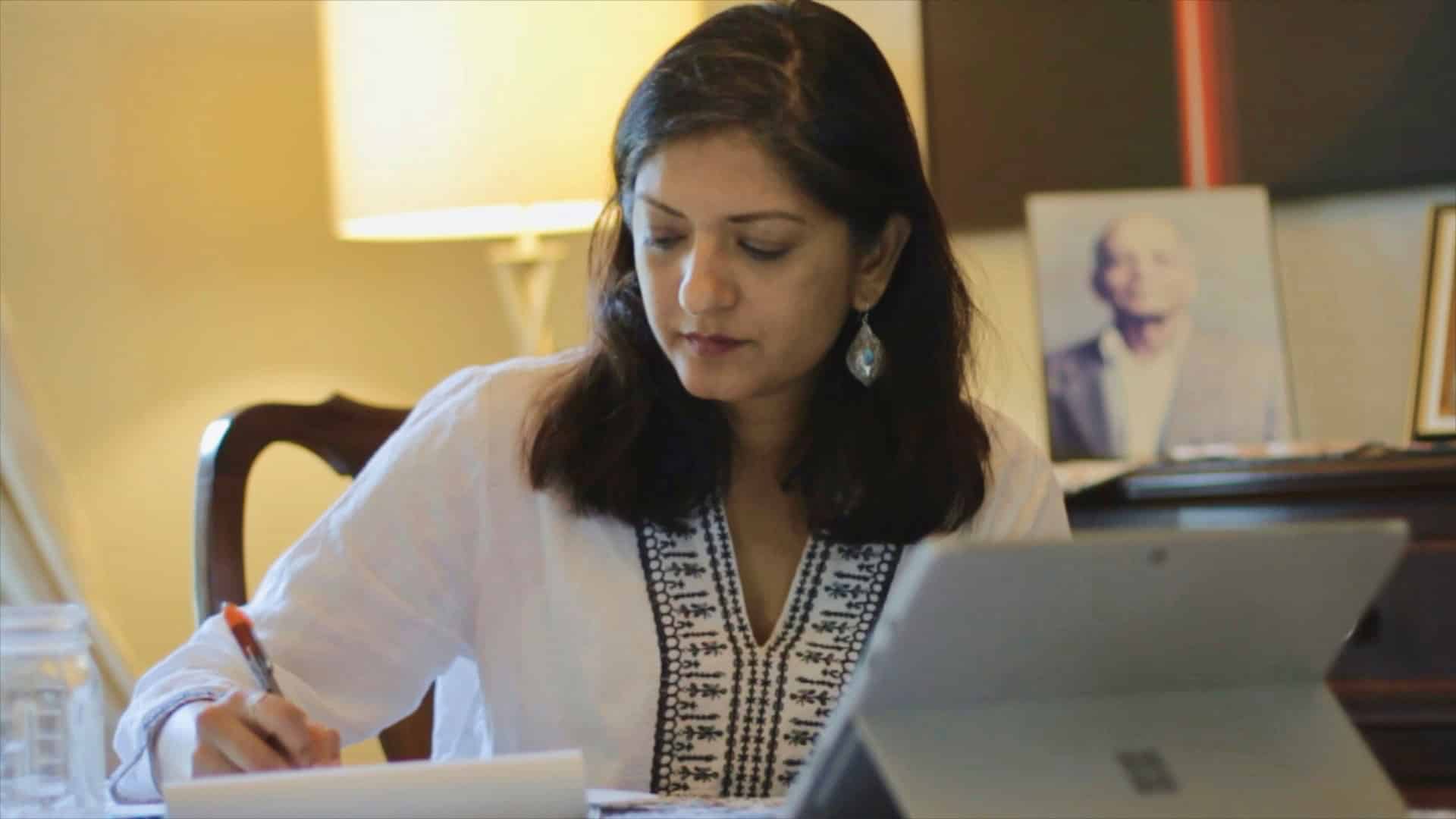

Now, with the state locked down due to the pandemic, she spends her days telephoning voters and hosting virtual town halls from her house in Glen Rock, where she is a councilwoman.

“The core of my campaign has been grassroots energy,” said Kreibich, a neuroscientist challenging two-term Representative Josh Gottheimer for the Democratic nomination. “The jury is still out, but we’re still meeting people in a different way.”

Like other liberal challengers around the country aiming to replicate Democratic U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s stunning 2018 victory in New York, Kreibich faces a dilemma: how to operate an insurgent campaign while trapped at home.

The coronavirus has eliminated the traditional campaign trail: no neighborhood canvassing, no meet-and-greets at the local diner or farmers’ market, no in-person town halls.

While all candidates, including presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, are struggling to adapt, the inability to connect with voters on the ground is particularly tough for challengers taking on established incumbents with high name recognition and hefty financial resources.

“We were canvassing in every nook and cranny of the district prior to the pandemic,” said Jamaal Bowman, a middle school principal in New York City and the leading challenger to Eliot Engel, a 16-term Democrat. “There’s nothing like having a conversation face to face with someone.”

The challengers have done their best to stay active.

Some have invested in new dialing systems and text messaging services to reach as many voters as possible. One silver lining: people under stay-at-home orders are more likely to pick up their phone.

Kreibich, whose campaign has made 65,000 calls and sent 40,000 texts since March, said she’s been surprised by how many meaningful conversations she’s had. Bowman said his campaign is making 10,000 calls a week.

‘DIFFERENT TACTICS’

Alex Morse, the 31-year-old mayor of Holyoke, Massachusetts, who is running against Democratic U.S. Representative Richard Neal, launched a six-part series of virtual town halls this week focused on the coronavirus.

“We just have to use different tactics and connect with voters in different ways,” said Morse, who was born four weeks after Neal, 71, was sworn into Congress in 1989. “If I do a coffee hour, there might be 20 or 30 people there – when I do a Facebook Live on a Tuesday night from my dining room, there could be 300 people watching.”

Backed by grassroots groups such as Justice Democrats, a liberal political action committee that helped propel Ocasio-Cortez to victory, the challengers have painted their opponents as out-of-step with their districts and with an increasingly progressive Democratic Party.

Bowman, for instance, has criticized Engel for remaining in the Washington area for weeks, even as his district recorded one of the country’s worst outbreaks.

In response, Engel’s campaign spokesman said the congressman has been “working every waking hour” to help constituents navigate the crisis.

Seeking to leverage their incumbency, the sitting lawmakers have highlighted Congress’ coronavirus response, including authorizing close to $3 trillion in additional spending to try to ease the human and economic toll of the pandemic. Engel’s campaign website notes New York hospitals received $5 billion in relief aid.

Fundraising could be a problem for insurgent candidates, though several challengers – most of whom rely on online, small-dollar contributions – said donations have not flagged, without offering specifics. Bowman’s campaign said it set a monthly record in April for new donors and total receipts.

The incumbents are sitting on much larger war chests. Neal, the chairman of the House’s powerful Ways and Means Committee, had $4.5 million on hand as of March 31, more than 30 times as much as Morse.

Many of the challengers’ narrow paths to victory also rely on motivating infrequent voters, including young and minority residents. The pandemic has forced postponements and prompted some states to turn to absentee balloting, a multistep process that may be daunting for some voters.

Two liberal candidates’ runs earlier this year could be instructive.

In Ohio, Morgan Harper abandoned plans to knock on thousands of doors in the days before a March 17 primary, when she was taking on incumbent Congresswoman Joyce Beatty. The election was delayed at the last minute by six weeks and converted to an all-mail vote.

Harper’s campaign shifted gears, hosting phone banks and delivering 4,000 absentee ballot applications to voters’ doorsteps. She still lost by 37 percentage points.

“This is a situation that plays more to an establishment candidate’s advantages,” Harper said. “That really hurt us quite a bit.”

The March 17 election went forward in Illinois, however, where liberal Marie Newman – who pulled canvassers off the streets days before – narrowly ousted conservative Democrat Dan Lipinski in a major win for progressives.

“We were worried,” Newman said. “When you are unseating an incumbent that has been in office for 15 years, you have to have constant voter contact.”

(Reporting by Joseph Ax in West Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and Susan Cornwell in Washington; Editing by Scott Malone and Daniel Wallis)

Continue with Google

Continue with Google