Shushannah Walshe is IJR’s editor at large. This is her personal essay on her own COVID-19 experience.

It was mid-March when I woke up at 2:30 a.m., feeling feverish. It was at the very beginning of the global pandemic, when COVID-19 had not yet ravaged the country, but stay-at-home orders were beginning to take hold.

It had been years since I’d had a fever. I probably would have ignored it and gone back to sleep, but the coronavirus got me out of bed. I took my temperature and it was 102 degrees. I woke my husband and told him I was going into the guest room to sleep in case I had “it.” I woke up later that morning with the same fever, fatigue, and a headache.

Several days later, I developed a tell tale coronavirus symptom: loss of all sense of smell and taste. This was the only symptom my husband experienced — we only realized it when we both could not smell a challah bread I had baking in the oven. Yes, I was attempting to bake bread, a quarantine hobby the rest of the country was also pursuing.

For weeks, I had a persistent pounding headache and could not taste or smell. As soon as my symptoms began, I tried to get a COVID-19 test. I called my doctor right away, but she explained I did not qualify for testing because I did not have a cough or any breathing issues, and we knew there were test shortages. She did tell me to stay isolated at home and to assume I had coronavirus. My 5-year-old daughter came down with a fever which, like mine, also lasted just two days, but my two other young children had no symptoms at all.

We are the lucky ones. That I got sick and recovered easily, comes with an uncomfortable feeling of gratitude and shock that is still difficult to process. When I see so many others suffering and dying from this same disease, it is hard to shake a guilty feeling. Why did I get it so mildly? I just do not know.

Weeks later, I began seriously regretting not pushing harder to get tested. I had wanted to listen to my doctor, but without a positive test, I could not donate plasma to help others fighting COVID-19. At the time, I was also scared to leave my apartment to get tested. I was panicked at the thought of accidentally infecting any of my neighbors, especially those that are elderly, during the short elevator ride and walk through my lobby.

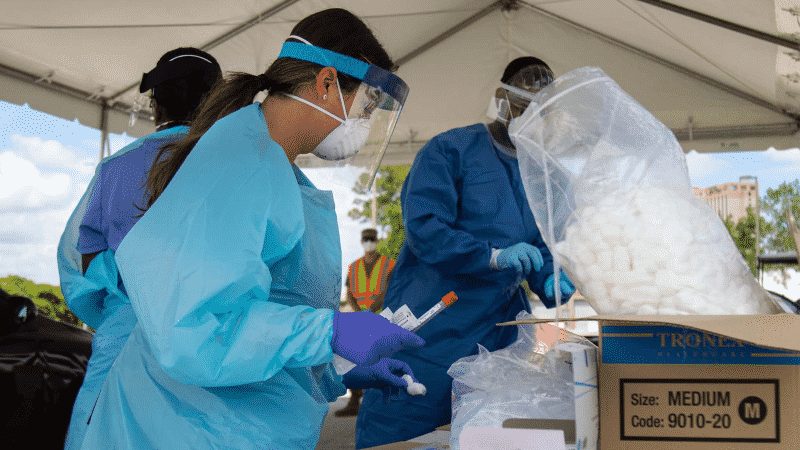

I was able to get an appointment for an antibody test at the end of April. I waited in line with my mask and gloves on, socially distanced from two other people. My blood was drawn in a tent outside of a doctor’s office by a friendly phlebotomist. I was out of my car for only about 15 minutes. My husband went three days later.

Five days later, a doctor called me and said he had “good news” for me, I had positive antibodies for COVID-19. Several days later, my husband also tested positive. This testing location did not test children younger than seven so I was not able to get results for my three children.

I knew it was good news. Now I can give plasma and I even have a date scheduled soon.

But, I really did not know what it meant for my family’s safety. I knew I was relieved and my anxiety around the insanity of the last few weeks calmed a bit. Was I right to feel that relief? There was so much confusing information, I decided to do some of my own reporting.

The reason much of the information on antibody testing is baffling is because this disease is new, according to Dr. Raymond Baer who is the Director of Clinical Pathology at Stamford Hospital in Stamford, Connecticut. Baer is currently overseeing and studying antibody testing at the hospital.

“Right now we are all learning and no one really knows,” Baer told me in a phone interview. “The thought and assumption is you had it and you got over it and having the antibodies means you have been exposed and you have protective antibodies. The assumption is you can not get it again.”

“So the assumption is you are over it,” he added. “These are the things I believe. I believe you had it, you have the antibodies and that means you had it in the past and it means you can’t get it again. Your body has combated the virus.”

Baer explained this is all part of the studies he is doing at Stamford Hospital.

“People are giving their plasma to other people who are sick and the assumption is something in [recovered people’s] blood is a neutralizing antibody, but these are all assumptions,” Baer said.

I also spoke with Dr. Farren Isaacs, a bioengineer at Yale who is using genomic technologies to study COVID-19.

“If you have an exposure and you overcome it, then, typically, you have an immune system that has developed antibodies to protect you against additional exposure,” Isaacs said. “Then your immune system is primed and has antibodies. It detects and mass produces the antibody and fights off the virus and, in that instance, you are protected.”

Of course that is great news for me right now, but what does it mean going forward? Baer said the question of “how long will you be protected” is still unknown.

“How long is your protection? Is it only a few months? Is it a year? Does it wear off? Is it a lifetime? No one knows. The assumption is now you are protected, but no one knows how long that will last….This is a new disease and there is a lot of weird stuff about it.”

Another important factor is the reliability of the antibody testing. Baer stressed that blood draw testing, as opposed to instant finger prick tests, are much more reliable.

Both Baer and Isaacs agreed that testing is quickly improving, but it is not perfect.

“Based on prior antibody tests, provided a person who is two weeks post symptoms, the IgG antibody test should be a good indicator of past exposure to COVID-19. That said, I wonder if there is a wrinkle in all of this because there are many coronaviruses floating around; there is a family of coronavirus,” Isaacs said.

“They are different, but closely related. Since the vast majority of us have been exposed to a coronavirus, could those prior exposures result in a false positive antibody test for COVID-19? Robust testing and either herd immunity or a vaccine are needed to protect the population.”

Isaacs added that he thinks the main reason there is still caution for those exposed to re-enter society is because the “scientific and medical community is still figuring this whole virus out and exactly how it is infecting people. As you can see there is a wide spectrum of symptoms and degrees of illness, people who are asymptomatic and a huge number of those of who have succumbed to this illness.”

“These things do take time to play out, even with really smart and capable teams of scientists and physicians going after these problems.”

So, while I am relieved and extremely grateful, my pandemic life has not changed that much.

I still wear a mask when I leave my apartment. With three young kids and no school, we are still very much mostly at home. I still wash my hands so often they are raw. I mostly only go out for walks or trips to the park with my children and the rare visit to the grocery store. (I’m not Cloroxing my groceries or deliveries, and for that, I feel lucky.)

I wear my mask because I want to respect my neighbors. It is not because I am scared that I or my family will contract coronavirus again, at least right now. I remain anxious and cautious about the unknown, about what we do not know. Just like the rest of the country, we are learning to live in the new normal, even if it is somewhat different.

Continue with Google

Continue with Google