What at one time was a stray relic found by a Colorado rancher has proved to be a treasure of the region’s Native American heritage.

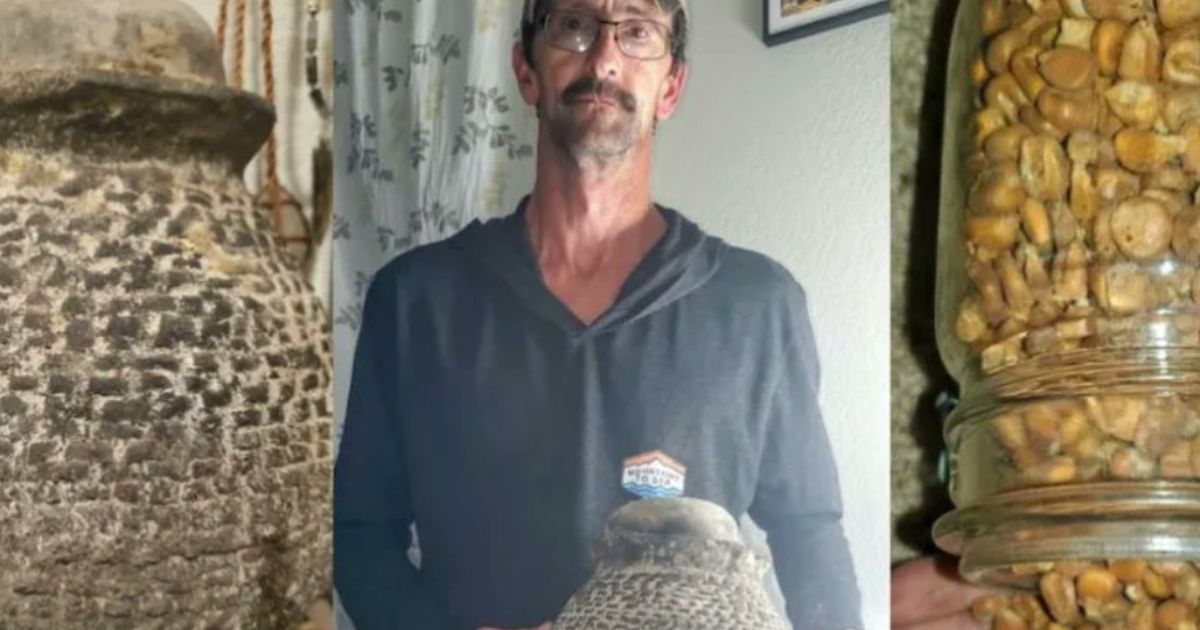

The relic — a clay pot — was acquired by Steve Campbell, a rancher and authority on ancient artifacts, in 2015 from a rancher who found it several years ago, according to AgWeb.

Although the pot itself tells a story, it was its contents that moved Campbell – about 5 pounds of corn that had been harvested nearly 1,000 years ago, preserved, and never eaten.

“Unbelievable and beyond rare,” Campbell said. “Never dreamed I’d see anything like this pot. No doubt, this corn was someone’s last harvest, and they never came back for it. The end.”

The pot was found roughly 50 years ago – even the rancher who found it wasn’t certain of the time frame – when the rancher spotted a rock overhang and a very odd “round rock” in the dirt near the overhang.

The rancher then found that the rock was a pot that, other than being disturbed by livestock, had been placed there perhaps a thousand years ago. The rancher took it home and set it on a shelf, where it remained for decades, according to AgWeb.

Campbell heard about the find and eventually bought it for an undisclosed price.

The 10-inch-tall pot had its lid still sealed, but a hole in the bottom — presumably made by livestock — allowed Campbell to access the corn within.

Campbell said the pot was made between 900 and 1200 A.D. by Puebloan people and still shows the fingerprint of the Native American woman who likely fashioned it.

“This is a dual-use, corrugated cooking and storage pot, and the lid was supposed to be used for a bowl. Basically, they had two containers in one,” Campbell said. “I’ve seen this design many times, and I’ve got a couple other objects with identical designs from around Mancos.

“It’s a coiled construction. They rolled out a piece of clay and then coiled it and pinched as they went up, kind of like connecting a bunch of snakes and pinching until they reached the lip. You can see clear thumbprints in the clay on several places. It was originally light gray, and used for cooking, and the heating marks are still easy to make out.”

Campbell said the pot was created for a purpose, not as art.

“We see this incredibly pretty pottery, and we think it was about something to look at. No. I’d estimate 90 percent of artifacts found today were utilitarian and related to survival.”

The people who made the pot “were probably living under that overhang area,” Campbell said, referring to the area near Mancos, Colorado, where the pot was found.

“If an archaeologist excavates that overhang, they’ll find remains of habitation,” he said. “That pot was placed in there and packed with 5 pounds of corn for a food source, maybe if something went wrong with the next year’s harvest. It was surplus, and they were depending on it. Something happened to those Indians, and they weren’t able to return.”

Despite everything that had happened, the pot’s contents had not rotted over time, Campbell said.

“The corn kernels are in about perfect condition. No moisture, no sun, and sealed in that pot for 1,000 years, the corn looks like you can’t believe,” he said, adding that he has given specimens to universities to study because the genetic makeup of what was grown 1,000 years ago has since been lost.

Finding corn that was suited to the area could improve what farmers can grow now.

“The scientists want to know how this particular corn grew so well and if it’s now extinct,” Campbell said.

He said the corn was grown not far from where it was found.

A curious rancher who stumbled into a forgotten cave searching for straying cows, Steve Campbell, discovered one of the most incredible Native American artifacts: a clay pot protecting well-preserved corn ? harvested 1,000 years ago.

Find out more ?https://t.co/by2hH5LznB pic.twitter.com/xZbScowZzw

— The Crop Trust (@CropTrust) January 26, 2022

“It’s in a small valley below another overhang,” he said, per AgWeb. “You get down low to the ground and look up the valley, and you can actually see the remains of the rows. How much corn were the Indians able to work? How much did it yield? I don’t know, but this spot is about three to four acres.”

Campbell has found other crops grown by Native Americans.

“I’ve found lots of beans. I once found a corn cob with some of the kernels still attached in a cave. I also found human feces at that site, and archaeologists came and took several specimens to measure diet. My buddy found a gourd-shaped watermelon at a site, and it was unbelievable because the black seeds inside grew when we planted them. Best watermelon I’ve ever tasted. The climate out here keeps things intact, and I’ve come across things that you’d swear were dropped yesterday,” he said.

Campbell said the relics are more than old pottery.

“I want future generations to always know about this pot. The people who made it were just like us, trying to grow and keep food to survive,” he said.

“It’s humbling to hold something in your hands that people saved for survival. In a lot of ways, this pot of corn may have been the divider between life and death for someone long ago. Nobody goes to all that effort and walks away from that much corn.”

This article appeared originally on The Western Journal.

Continue with Google

Continue with Google