U.S. Supreme Court justices on Wednesday will consider whether public schools can punish students for what they say off campus in a case involving a former Pennsylvania cheerleader’s foul-mouthed social media post that could impact the free speech rights of millions of young Americans.

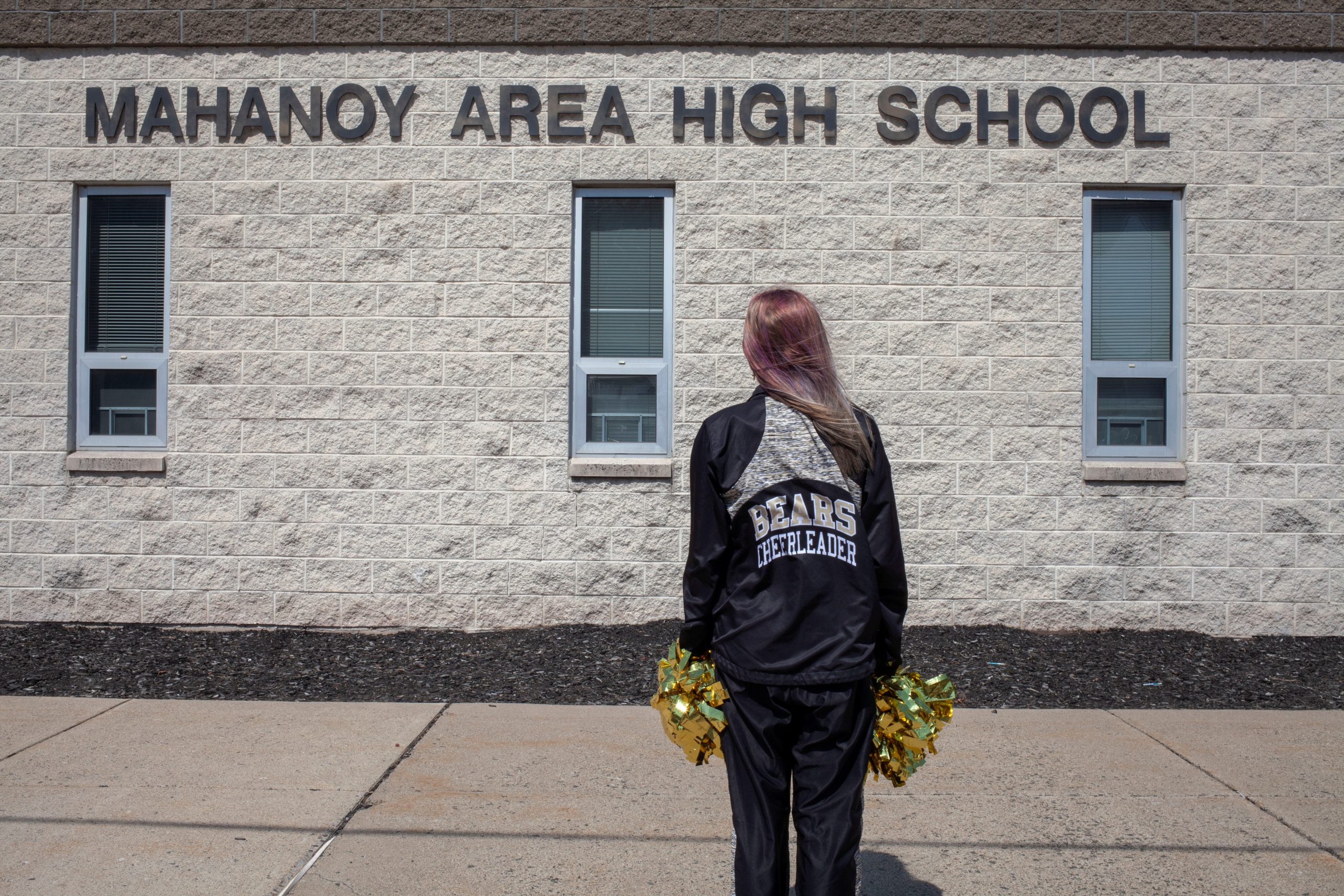

The nine justices are set hear arguments in an appeal by the Mahanoy Area School District of a lower court ruling in favor of Brandi Levy that found that the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment guarantee of freedom of speech bars public school officials from regulating off-campus speech.

Many schools and educators, supported by President Joe Biden’s administration, have argued that ending their authority over students at the schoolhouse gates could make it harder to curb bullying, racism, cheating and invasions of privacy – all frequently occurring online.

The American Civil Liberties Union, representing Levy, has argued that students need protection from censorship and monitoring of their beliefs.

Under a 1969 Supreme Court precedent, public schools may punish student speech that would “substantially disrupt” the school community. Levy’s case will determine whether this authority extends away from school.

Peeved because she was denied a spot in a tryout for the varsity cheerleading team after being a member of the junior varsity squad as a ninth-grader, Levy – age 14 at the time – made a Snapchat post that set the case in motion.

On a Saturday while at a convenience store in Mahanoy City in Pennsylvania’s coal region, she posted a photo of her and a friend raising their middle fingers, adding a caption using the same curse word four times to voice her displeasure with cheerleading, softball, school and “everything.”

As a result, Mahanoy Area High School banished her from the cheerleading team for a year. She and her parents sued, seeking reinstatement to the squad and a judgment that her First Amendment rights had been violated. A judge ordered Levy’s reinstatement, finding that her actions had not been disruptive enough to warrant the punishment.

The Philadelphia-based 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals last year went even further, deciding that the Supreme Court’s 1969 precedent, known as Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, does not apply to off-campus speech and that the First Amendment prohibits school officials from regulating such speech.

The Supreme Court, which has a 6-3 conservative majority, has shown sympathy toward free speech claims in important cases in recent years.

Now 18 and a college student studying accounting, Levy said the case has taught her that school administrators should have limits on what they can enforce.

“If a student is targeting the school or threatening someone or bullying someone, that’s when I feel the school should step in. But for a student to express themselves and get in trouble for it, I feel like that’s not right,” Levy said in an interview.

The court’s eventual decision would affect public schools, as governmental institutions, but not private schools.

A ruling in the case is due by the end of June.

(Reporting by Andrew Chung in New York; Editing by Will Dunham)

Continue with Google

Continue with Google