The U.S. political convention, a presidential campaign ritual dating to the 1830s, is being reinvented on the fly after being short-circuited by the coronavirus pandemic – much like the campaign itself.

Here is a look at how the Democratic and Republican conventions will be different this year – and maybe for campaigns to come.

SEIZING THE SPOTLIGHT

There will be no roaring crowds of delegates in a cavernous hall, no balloon drops or wall-to-wall parties. Both Democrats and Republicans will offer mostly virtual programs featuring speeches and events from around the country.

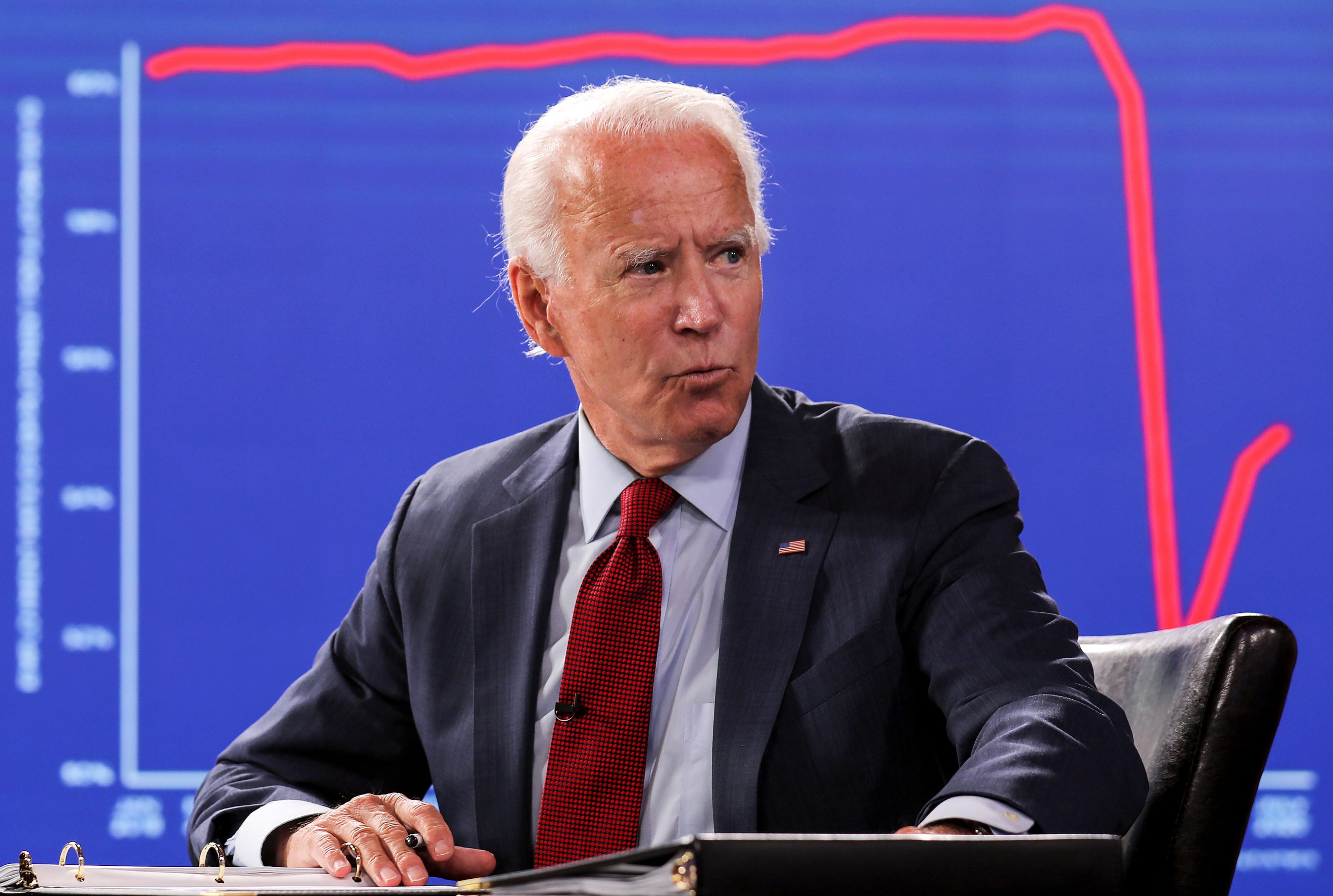

Nevertheless, the Aug. 17-20 Democratic National Convention could give presumptive nominee Joe Biden his first big, attentive audience in months, said Julian Zelizer, a political historian at Princeton University.

Though Biden leads Republican President Donald Trump in opinion polls leading up to the Nov. 3 election, the Democratic former vice president has been largely booted off the campaign trail by the pandemic. Trump, meanwhile, has continued to command heavy media attention with his White House briefings and campaign events.

That puts increased significance on Biden’s televised acceptance speech, the traditional starter’s gun for the final sprint to the election.

“That could be more valuable this year than in other years, particularly for Democrats, because most people have not been paying as much attention to the nominee lately and he hasn’t been campaigning,” Zelizer said.

For Trump, his speech could be a chance to move beyond the debate about his handling of the coronavirus and allow him to present his broad vision for a second term, said Ford O’Connell, a former Florida Republican congressional candidate who consults with the Trump campaign.

“The campaign believes if they can get past that hurdle, it’s easier to make your other points,” he said. “This is the place for Trump to make his case about where he wants to take the country.”

The prime-time speeches will be more intimate. Biden will speak from his home state of Delaware, not Milwaukee, the host city for a mostly virtual convention. Trump, who will be renominated at a small Republican convention on Aug. 24 in Charlotte, North Carolina, is expected to deliver his later that week from somewhere in Washington.

PUSHING PARTY MESSAGE

The reimagined format of the back-to-back conventions will force the parties to try to find a more compelling way to get their messages across.

Speeches by party stalwarts and rising stars will be delivered remotely from around the country. Democrats have designed a virtual video control room to take in hundreds of feeds, with the potential to interact with Americans nationwide.

“They aren’t confined to one stage or one place, so they will be forced to innovate,” said Kelly Dietrich, a Democratic strategist who has been running training programs on virtual campaigning for political candidates and staff.

The challenge will be to generate excitement and motivate the party faithful while encouraging independents and infrequent voters to take a look.

One plus for party unity: The virtual nature of the conventions will minimize the chance for signs of discord and unscripted moments.

In 2016, heckling from supporters of U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders disrupted the first night of the Democratic convention that nominated Hillary Clinton. At the Republican convention, U.S. Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, Trump’s top rival for the nomination, drew boos when he refused to endorse Trump and told delegates from the stage to “vote your conscience.”

This year, “you don’t have to worry about booing,” Dietrich said.

END OF AN ERA?

Critics have assailed conventions in recent years as tightly scripted party advertisements drained of political drama and relevance. Predictions of the imminent demise of the traditional American political convention came true in 2020 thanks to the pandemic.

Experts are uncertain whether that will be a permanent change.

“There may still be conventions, but I don’t think they will fundamentally be the same,” Zelizer said.

Longtime Democratic strategist Robert Shrum said he expected to see them back as strong as ever.

“It’s the nominee’s one chance for totally unmediated communication with voters. I don’t think people will happily give that up,” Shrum said.

After the pandemic, he said, “people will want to return to the things they have done in the past.”

(Reporting by John Whitesides; Editing by Colleen Jenkins and Jonathan Oatis)

Continue with Google

Continue with Google