A 57-year-old Maryland resident has survived after receiving the first successful pig-to-human heart transplant. The operation has prompted scientists to consider the various applications of this form of surgery amid an ongoing organ shortage.

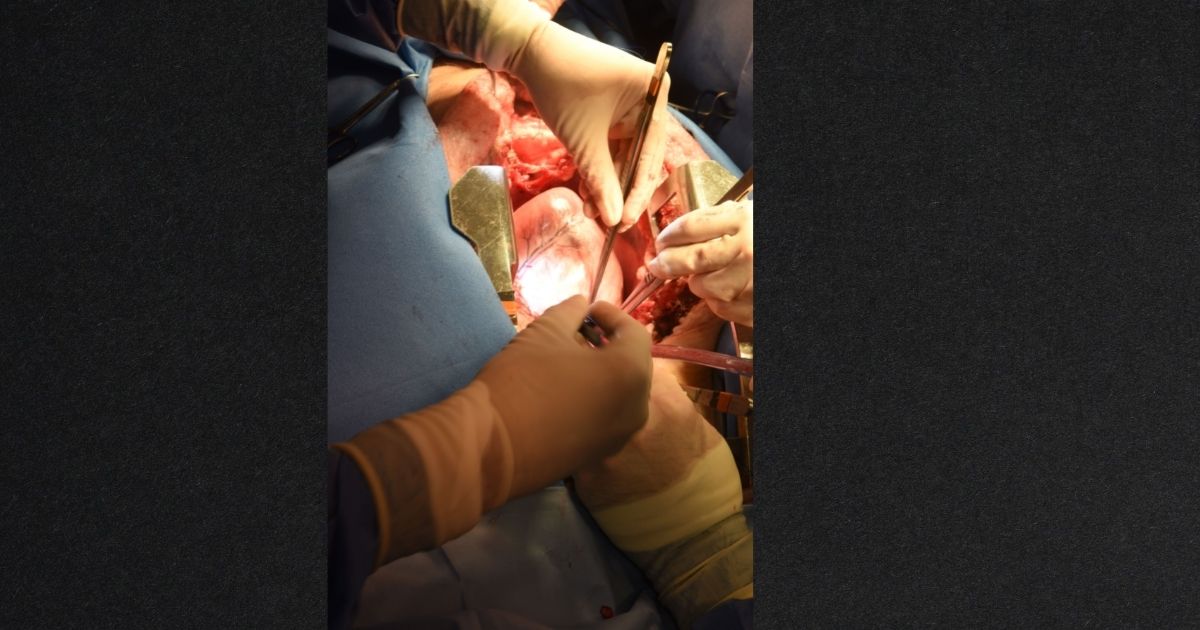

Following a New Year’s Eve emergency approval from the United States Food and Drug Administration, University of Maryland School of Medicine faculty scientists and clinicians carried out the Jan. 7 experimental surgery on patient David Bennett.

The University of Maryland Medical Centre announced the surgery in a Jan. 10 news release, noting that Bennett fared well three days following the “historic” operation.

“This was a breakthrough surgery and brings us one step closer to solving the organ shortage crisis. There are simply not enough donor human hearts available to meet the long list of potential recipients,” Bartley P. Griffith, the doctor who transplanted the heart, said. “We are proceeding cautiously, but we are also optimistic that this first-in-the-world surgery will provide an important new option for patients in the future.”

According to the center, health care workers will be monitoring the patient to determine if the genetically modified pig heart does indeed help save the lives of transplant recipients.

The FDA approved the surgery under its “compassionate use” provision, considering that using the pig heart was the sole option for the patient, the news release stated.

According to the news release and reporting from the Wall Street Journal, Bennett was dying, hospitalized and bedridden, ineligible to receive a human heart transplant.

“It was either die or do this transplant. I want to live. I know it’s a shot in the dark, but it’s my last choice,” Bennett said before his surgery, according to the news release.

Blacksburg, Virginia-based regenerative medicine company Revivicor supplied the genetically modified donor pig to the UMSOM lab. The pig’s heart was genetically modified to ensure that it could withstand any rejection from Bennett’s immune system.

According to the university, the process spanning ten gene edits involved taking out three genes that trigger antibody rejection of the pig organs from the human’s immune system.

Genetic engineers further inserted into the genome six human genes that facilitate the acceptance of the pig heart into the human’s immune system. According to the news release, the gene modifiers also “knocked out” a gene that could have led to excessive pig heart tissue growth.

During the operation, university physician-scientists deployed a new experimental counter-rejection drug formulated by Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals in tandem with regular anti-rejection drugs for immune system suppression and thwarting the rejection of the foreign organ, the news release stated.

“We have crossed the Rubicon,” NYU Langone Transplant Institute Director Dr. Robert Montgomery said, according to the Wall Street Journal. He was not involved with surgery. “We are trying to make sense of it and where to go next.”

According the Wall Street Journal report, the surgery has revived discussions on the possibility of future interspecies transplantation — or xenotransplantation — trials and the eligibility for such surgeries.

The practice was first tried in the 1980s on an infant known as Baby Fae, who was born with a fatal heart condition. The girl, whose real name was Stephanie Fae Beauclair, was given a baboon heart at Loma Linda University in California. After the young patient died within a month of the procedure due to immune system rejection of the foreign heart, interspecies transplants were largely abandoned, according to the UM news release. However, the release added, pig heart valves have been used for many years to replace human heart valves.

The Journal reported that the Maryland surgery is a milestone in scientists’ attempts to find solutions to the chronic organ shortage crisis.

“One procedure does not in and of itself mean this is going to be a safe and effective intervention,” Hastings Center bioethics scholar Karen Maschke said, according to the Wall Street Journal. “We have to make sure we get good evidence that the risks humans will be taking are worth taking.”

Dr. Griffith told the newspaper that while the University of Maryland team and researchers from other institutes are working to secure FDA approval for any future pig-to-human heart transplantation trials, his focus is on caring for Bennett.

This article appeared originally on The Western Journal.

Continue with Google

Continue with Google