After surviving two strokes at age 27, Olivia Colt threw herself into starting a catering business, a lifelong dream. Ten years and another stroke later, she had built Salt & Honey Catering Plus Events into a thriving operation in downtown Oakland.

Now with the coronavirus pandemic forcing cancellations of her customers’ weddings and events, she has slashed her staff from 25 to six and tried to drum up new business by selling groceries online. She secured a $100,000 forgivable loan under the U.S. Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and another $150,000 loan under a federal program usually used for natural disasters. She expected the money to get her through just a few months of hardship.

But the hardships are dragging on.

“I’ve applied for all the grants and loans, I have maxed out my credit card, used my company’s reserves, spent my savings,” she said.

Colt now fears she may have to shutter her business permanently. Many small businesses nationwide are reaching similar breaking points in an economy with the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression. Small firms have survived the pandemic so far with a mix of government aid, forbearance on debt and rent and creativity in selling to an increasingly homebound and financially distressed populace.

As the first wave of U.S. aid runs short – and landlords and lenders lose patience – lawmakers are in tense negotiations over a new round of stimulus, which could include more money for small business.

The White House did not respond to a request for comment.

Most firms have already run out of the money they secured from the $600 billion Paycheck Protection Program, according to a survey released this week from the National Federation of Independent Business, a leading trade group for small U.S. firms.

The federation also found in early July that 23% of respondents expected to be out of business within six months unless economic conditions change..

Bill Phelan – who tracks small business borrowing for credit reporting firm Equifax Inc. – says defaults are up sharply to about 2.7% of small business debt. By next year, his models are predicting a rise to 5% or 6%. (For a graphic on business default trends, click https://tmsnrt.rs/2CVqyzZ )

Defaults peaked at 6.35% in 2009, during the Great Recession, Phelan’s data shows. Then, U.S. government stimulus totaled less than $1 trillion – compared with $3 trillion so far since the pandemic hit.

“The forbearance and the PPP have helped out a ton, but they can’t go on forever,” he said.

Without a vaccine to fight new waves of infection, Phelan expects double-digit rates of default in hard-hit sectors including hospitality, food service, and retail.

Business owners like Colt are hard-pressed to stay open without piling up more debt – with no guarantees of success.

“Is it worth taking on more debt, if your business can’t survive?” she asked.

SURVIVAL STRUGGLE

Colt, whose mother and grandmother immigrated from the Dominican Republic, moved her kitchen in May to a cheaper space in industrial West Oakland. Her previous landlord initially had been understanding but soon started demanding payments she could no longer afford.

The new business she’s cobbled together isn’t enough. Sales are a third of her pre-pandemic projections. So now she’s talking to accountants and lawyers about how to shut down her business – while praying it never comes to that.

Similar dramas are playing out nationwide, especially in states where surges of infection are forcing local officials to tighten restrictions on businesses. Worried consumers are also choosing to stay home and spend less, data from JP Morgan credit-card purchases show.

That’s making business owners take a hard look at shutting down for good, said Ari Takata-Vasquez, who leads the Oakland Indy Alliance, a group of about 500 small firms in Northern California, including Colt’s.

“Three weeks ago I noticed a shift in energy,” Takata-Vasquez said. “A lot more people seem to have closure on the table.”

Some 44% of members surveyed recently have only enough money to operate for three months or less, Takata-Vasquez says. To help forestall a rash of failures, the Oakland organization this week launched a campaign to raise $4 million from donors to finance grants to local firms, with priority given to businesses owned by immigrants and people of color.

Business owners who brave the economic conditions still face the ever-present threat of a health-related shutdown. Colt closed her catering operation for two weeks in May, when a worker called in with a fever, to allow her staff to get tested and wait for results. The tests did not find coronavirus.

Farley’s East cafe, which used to sell lunches and lattes to Oakland’s downtown office workers, has now burned through its PPP funds and gets by through a contract with a nonprofit organization that buys meals from restaurants and distributes them to those in need. Co-owner Chris Hillyard says the cafe’s long-term viability depends on office buildings reopening – an outcome looking unlikely anytime soon as California leads U.S. states in COVID-19 infections and area schools won’t reopen until the surge subsides.

“We’re hanging on,” Hillyard says.

WHAT NEXT?

Thousands of miles away in Florida, toy importer Basic Fun Inc says sales are rising sharply as big retailers including Walmart Inc and Target Corp return to more normal operation. But chief executive Jay Foreman doesn’t have the $10 million he needs to buy the merchandise to meet that demand.

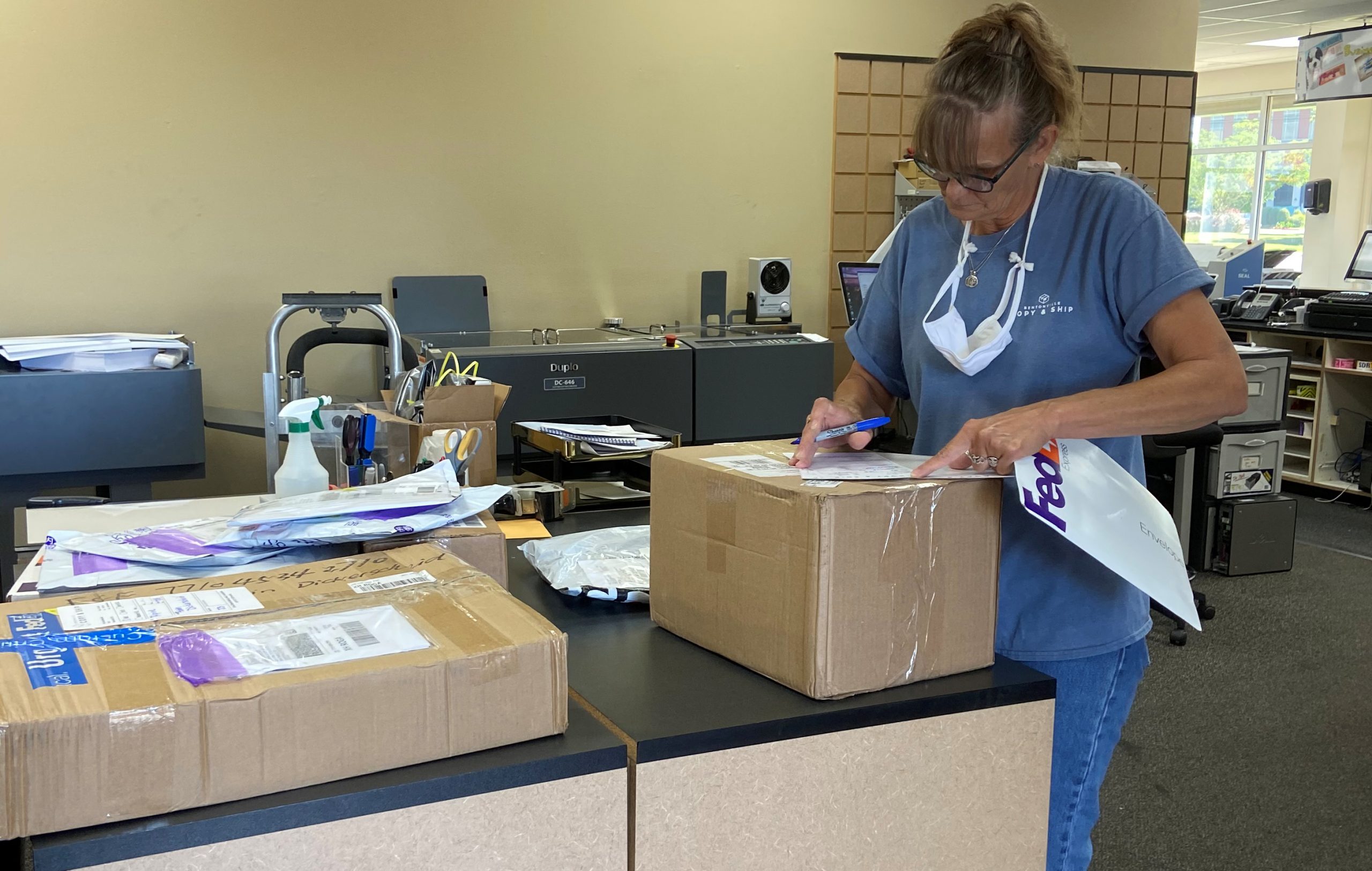

In Bentonville, Arkansas, Holly Thomas has lost money since February on her printing and shipping company, a family business started by her father three decades ago. She’s been paying her five employees, including herself, thanks in large part to a PPP loan of about $55,000. She’s trying not to dip into the additional $150,000 she’s borrowed from the federal Economic Injury Disaster Loan program.

Revenue for this year through July 24 is down 35% compared from last year. She gave up some storage space to reduce her rent costs by a third, but her health insurance expenses increased by 8% in April. At the current pace, she expects to be out of funds by October or November.

And then what? She worked previously in the film and music industries, and worries it could be hard to find a job in any industry with millions of people unemployed.

“A lot of people are facing that same question – what do I do next?” she said. “I know I’m going to be competing with so many people for just a handful of available jobs.”

(Reporting by Ann Saphir and Jonnelle Marte; Additional reporting by Rajesh Kumar Singh and Tim Aeppel; Editing by Dan Burns and Brian Thevenot)