Liz Peasley, a special education aide in the rural Grand Coulee Dam School District in Washington State, drives 10 miles from her home on the Colville Indian Reservation just to get a workable cellphone signal.

Now, with schools shut down until the fall because of the coronavirus pandemic, Peasley – who doesn’t own a computer or tablet – is confronting the same dilemma millions of others in the United States are facing: How to ensure kids trapped at home receive some version of an education if they can’t get online.

“I’m super overwhelmed,” said Peasley, who has three kids between the ages of 10 and 13. “I’m a single mom – it’s tough for us on a good day.”

Some 14% of school-age children, or 7 million, live in a home without high-speed internet, many in less populated areas that lack service or in low-income households that cannot afford it, a 2018 Department of Commerce study found.

In many cases, households may rely only on a cellphone, or may share a single device among several children, making it challenging to complete schoolwork even in the best of times.

While the digital divide is not a new phenomenon, the coronavirus outbreak has laid bare the technological inequities that bedevil rural and impoverished school districts, including Grand Coulee, where two-thirds of the approximately 720 students – many Native American – are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

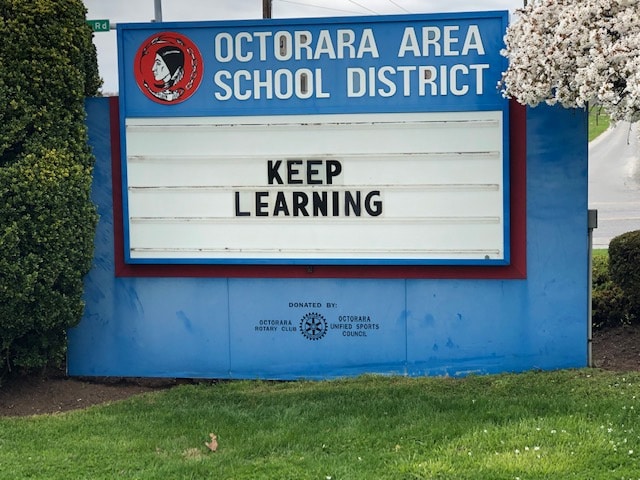

Now educators worry those disparities will turn achievement gaps into an “achievement chasm,” in the words of Michele Orner, the superintendent of the rural Octorara Area School District in Pennsylvania.

Some districts have reverted to earlier technologies, with staffers delivering paper packets along with meals for needy families. Some schools have stationed buses transmitting mobile wireless signals in neighborhoods; others have encouraged students to park near the school on the weekend and use the wireless network to download necessary materials.

But officials warn some kids will be left behind no matter what. Those concerns have only deepened as the coronavirus-forced hiatus has grown from weeks to months.

Thirty-seven states have either mandated or recommended that public schools serving more than 40 million students remain closed for the rest of the academic year, according to a running tally by the news publication Education Week.

Some states have already warned their schools may not reopen after summer. Washington State Governor Jay Inslee, for instance, encouraged school officials to start preparing in case the shutdown stretches into the fall.

‘SUMMER SLIDE ON STEROIDS’

The U.S. government provides some $4 billion each year to schools and libraries to increase broadband access, but the program does not permit them to use funding to extend offsite access.

“Those students that can’t do online learning are falling further behind,” said John Windhausen, the executive director of the Schools, Health & Libraries Broadband Coalition. “It’s going to cause a real problem, because the skills that students learn (in class) build off of each other.”

The risks are particularly acute for students with special education needs, including those who have individualized instruction plans that may not be suited for distance learning.

Some districts have hesitated to transition fully online out of fear that doing so would expose them to legal liability for failing to provide equitable education to all students. The Northshore School District in Washington State, one of the first in the country to close in early March, launched an online program immediately but put it on hold for two weeks to address equity concerns.

A lack of training or equipment means many rural or low-income districts are also less able to rely on online instruction.

“The degree of being able to move to online learning at a moment’s notice is totally dependent on the wealth of the district,” said Daniel Domenech, the executive director of the national School Superintendents Association. “At best, maybe 40 or 50% of districts are able to do that.”

In Bronxville, the affluent New York City suburb that saw the state’s first major outbreak in March, the school district has many advantages that poorer systems do not: Engaged parents, a student population that has near-universal internet access, and plenty of laptops to distribute to families in need.

“I’m in a fortunate district,” said Schools Superintendent Roy Montesano.

Many others are not so fortunate.

In Pennsylvania’s Octorara district, where students receive a Chromebook laptop starting in seventh grade, Orner, the superintendent, said she concluded that going back to pencil and paper would shortchange her kids.

Around one-quarter of her students lack high-speed Internet access, so the district recently bought 100 iPhones – Orner secured a $9,500 emergency state grant to cover the cost – for students to use as mobile hotspots.

But she acknowledged that the most vulnerable students are also the likeliest to fall behind even further.

“We talk about the summer slide,” she said, referring to the months between school academic years that sometimes causes students to slip backward. “Imagine the summer slide on steroids.”

As school districts grapple with new challenges, they look for solutions wherever they can. Grand Coulee Dam just started to employ some distance learning this week by setting up Google Classroom for those families able to access it and loaning out some Chromebooks, even as it continues to rely on pencil and paper classwork for students without internet.

Those packets, however, have to be carefully curated to ensure kids in poor households have everything they need.

“You want them to measure something, you better put in a ruler,” said Pam Johnson, a ninth-grade Grand Coulee Dam teacher. “You want them to color something, you better throw in a packet of crayons.”

(Reporting by Joseph Ax in New York; Editing by Scott Malone and Aurora Ellis)